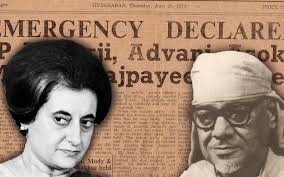

On June 12, 1975, the Allahabad High Court delivered a bombshell verdict that would alter India’s democratic trajectory. Justice Jagmohan Lal Sinha found then-Prime Minister Indira Gandhi guilty of electoral malpractices in her 1971 Rae Bareli election – including using government resources for campaigning and bribing voters – and invalidated her seat. The judgment, coming just months after the landmark Kesavananda Bharati case that limited parliamentary power, triggered a chain reaction: within days, Indira Gandhi imposed the Emergency, suspending civil liberties and jailing opposition leaders.

Nearly half a century later, this watershed moment remains deeply relevant. Today, as India debates electoral integrity, judicial independence, and the balance between executive power and accountability, the 1975 verdict serves as both a cautionary tale and a benchmark. The judgment’s legacy echoes in contemporary political discourse – from Supreme Court rulings on election reforms to heated debates about authoritarian overreach. This article revisits the historic case through court documents and expert analyses, examines how it reshaped India’s constitutional framework, and explores why its lessons about power, accountability, and democratic safeguards matter more than ever in today’s political climate.

1. The Petition by Raj Narain

The legal challenge was brought by Raj Narain, a prominent socialist leader, who had been trounced by Mrs. Gandhi in Rae Bareli by over 110,000 votes in March 1971 . Viewing the result as tainted by misuse of office, he filed a petition in April 1971, accusing her of:

Employing a government official, Yashpal Kapur, as her election agent while he was still in service

Using district magistrates, police, public works staff, loudspeakers and rostrums funded by state resources during campaign events

Raj Narain also alleged inducements like distribution of blankets, liquor, and transportation assistance to voters. However, the court did not uphold these claims.

2. Key Findings by the Allahabad High Court

On June 12, 1975, Justice Sinha handed down a verdict that dismantled—on two principal grounds—Mrs. Gandhi’s electoral legitimacy:

a) Employment of a government servant as election agent

Yashpal Kapur, a gazetted officer in the PM’s Secretariat, was appointed as Indira Gandhi’s election agent on February 4, 1971. Evidence showed that he performed campaign duties even before his resignation became effective on January 25 .

b) Use of state machinery for campaign logistics

The court found that official resources—district magistrates, police personnel, infrastructure—were used to set up stages, loudspeakers, barricades and publicize Ms. Gandhi’s campaign events on February 1 and 25, 1971 .

These two offenses violated Section 123(7) of the Representation of the People Act, 1951, and were declared corrupt practices that invalidated her election .

Charges Dismissed

Other accusations—bribery, distribution of blankets or liquor, use of airplanes, or religious appeals including symbolism—were not upheld. Justice Sinha found no compelling evidence .

3. Sentence and Political Fallout

Justice Sinha declared Gandhi’s 1971 victory null and void, ordered her removal from the Lok Sabha, and barred her from contesting any election for six years . He also mandated that Congress (R) appoint a new prime minister within 20 days .

Chief Justice NV Ramana later praised the ruling as a courageous stand that shook the nation .

4. Appeal and Supreme Court Stay

Indira Gandhi immediately appealed to the Supreme Court. A vacation bench granted a conditional stay on June 24, 1975, permitting her to retain the prime ministership but stripping her of MP privileges—no vote, no salary and no speech in Parliament .

Notably, this partial relief did not fully uphold her authority, and unrest mounted both within the ruling party and across opposition ranks.

5. Declaration of the Emergency

On June 25, 1975, citing threats of internal disturbance, President Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed—on Indira Gandhi’s advice—declared a national Emergency under Article 352 .

Civil liberties were suspended. Press censorship was imposed. Thousands of opposition leaders, activists and journalists were arrested. Political expression was curtailed, including measures like mass sterilizations under Sanjay Gandhi’s campaign .

During the Emergency (June 1975–March 1977), Parliament retroactively shielded Indira Gandhi’s election from courts through sweeping amendments.

6.Constitutional Changes: 39th Amendment

To pre‑empt judicial review of her election, Parliament passed the 39th Amendment on August 10, 1975, adding Article 329A. It removed the legal jurisdiction of courts over the election of MPs, Prime Minister and Speaker .

This attempt at constitutional self‑immunity provoked a robust response. In November 1975, the Supreme Court refused to uphold immunity for current election cases, though it struck down certain aspects of Article 329A while restoring Gandhi’s political position .

7. Supreme Court Verdict and Overturn

On November 7, 1975, the Supreme Court delivered its final verdict. It:

Overturned the Allahabad High Court’s judgment that had declared Gandhi’s election void

Re-validated her election expenses and campaign legitimacy

Confirmed Yashpal Kapur’s resignation timing and innocence of Section 123(7) offense

Limited its strike-down to only Article 329A(4), upholding much of the Emergency-era legislation

This decision placated the constitutional crisis, allowing Mrs. Gandhi to remain in office.

8. Legacy and Lasting Lessons

This episode left deep scars on India’s democratic experiment:

It showed how executive power can be checked by the judiciary—but also how democracy can be undermined when such checks are overridden

It established that even the prime minister is not above election law

It revealed how constitutional procedures may be manipulated to shield officeholders

The imposition of Emergency served as a grim lesson in the fragility of civil rights

Judicial courage, particularly Justice Sinha’s, remains a proud moment in India’s legal history

In 1977, voters enforced accountability. The Emergency-era Congress (R) was defeated, Indira Gandhi herself lost Rae Bareli to Raj Narain, and the Janata Party ascended. It underscored the enduring power of democratic will over authoritarian impulses.

Conclusion

The Allahabad High Court’s June 12, 1975 verdict stands as a milestone. It upholds the sanctity of electoral law and underlines that misuse of state machinery is no trifling offense. It also reminds us that democracy demands constant vigilance. Courts must be ready to challenge entrenched power, and citizens must hold leaders accountable.

While history often views Indira Gandhi’s Emergency rule with controversy, the original finding of electoral malpractice remains a symbol of judicial independence and the resilience of democratic institutions.

For students of governance, this saga is a case study in:

Balancing executive authority and judicial oversight

Preserving civil liberties amid political crises

Ensuring that constitutional amendments do not override democratic checks and balances

From the courtroom of Allahabad to the corridors of power in Delhi, this judgment underscored that in a democracy, no one—no matter how high—can be immune from its laws.

References:

State of Uttar Pradesh v. Raj Narain, verdict and aftermath

Thank you for exploring this critical chapter in India’s democratic evolution.